Rosenut apdaila. Idealios būklės, komplekte dygliai, trumpikliai, gamyklinis įpakavimas. 1500EUR.

Majik 140

A floorstander with the power to move you

A full-range yet compact floorstanding speaker, Majik 140 will bring your music to life without dominating your room.

High frequency precision and wide dispersion are provided by the 2K Driver Array featured across the Majik range, while separate bass and mid drivers ensure musical accuracy at lower frequencies.

Majik 140 provides great value straight out of the box, as well as offering higher levels of performance through a range of upgrade options, from simple bi-wiring through to a fully Aktiv configuration within an Exakt system.

Majik 140

Key features

2K Driver Array houses the two high frequency drive units

2K Driver Array houses the two high frequency drive units High quality separate bass and mid drive units

High quality separate bass and mid drive units High quality custom-designed passive crossovers

High quality custom-designed passive crossovers Simple upgrade path from single to multi-wiring/amping to fully Aktiv configuration in Exakt system

Simple upgrade path from single to multi-wiring/amping to fully Aktiv configuration in Exakt system Bass reflex port with rifled design for extended bass

Bass reflex port with rifled design for extended bass Solid aluminium upgrade stands available

Solid aluminium upgrade stands available Standard and high gloss real wood veneer or bespoke high gloss colour finishes

Standard and high gloss real wood veneer or bespoke high gloss colour finishes

Technical Specifications

Passive floorstanding loudspeaker

| Features | |

| Speaker Type | 4-way floorstanding |

| Crossover | Analogue passive |

| Bass System | Ported bass reflex |

| Exakt | Compatible with Exaktbox |

| Space Optimisation | Yes – with a Linn Network Music Player |

| Connections | |

| Binding Posts | x4 |

| Drive Units | |

| Tweeter | 16 mm silk dome |

| Midrange | 30 mm PU dome |

| Bass | 160 mm doped paper |

| Lower Bass | 160 mm sandwiched cone |

| Finishes | |

| Standard Finishes | Black Ash, Rosenut, Walnut, Cherry, Oak, White |

| High Gloss Finishes | Piano Black, Rosenut, Walnut, Cherry, Oak, White |

| Custom Finishes | Yes – match any colour |

| Dimensions | |

| Cabinet Volume | 40 litres |

| Width | 250 mm |

| Height | 975 mm |

| Depth | 335 mm |

| Weight | 21.3 kg (including base) |

Linn Majik 140 loudspeaker

Design The Majik 140 incorporates Linn’s 2K tweeter-supertweeter array, derived from the 3K and 4K arrays used in Linn’s more expensive models. The 2K comprises a 1.17″ (30mm) tweeter with a soft dome of polyurethane elastomer covering the 1.5–6kHz range, and a 0.5″ fabric-dome supertweeter for frequencies above 6kHz. Below this are two 6.5″-cone units that look identical but are not. The upper unit, which covers the region below 1.6kHz, uses a doped-paper cone and operates in a sealed enclosure. The lower unit is a dedicated bass driver with a glass-fiber-and-composite cone that operates in its own enclosure, vented to the rear, and reinforces the output of the midrange unit below 200Hz. The speakers are supplied with a pair of foam bungs which enable the user to plug the rear port for setups where the speakers are placed flush against a rear wall.

The Majik 140 is fitted with metal spike feet that are easily adjustable for precise leveling. Also available is an optional stand ($580/pair, not supplied for review) made from a single billet of aluminum, which is nearly five times heavier than the standard wooden plinth. Phillip Budd, Linn’s senior acoustic engineer, claims that this heavy plinth improves the Majik 140’s performance.

The Majik 140 is available in standard finishes of Black Ash, Rosenut, Walnut, Cherry, Oak, and White; high-gloss custom finishes are available for another $950/pair. My Walnut samples were attractive, but I have a soft spot for the elegant Cherry of my Majik 109s.

Sound

Sound

The Majik 140 can be single-, bi-, tri-, or quadwired, and single-, bi-, tri-, or quad-amped. I used a single amplifier and a triwire set of Acarian Systems Black Orpheus speaker cables. As I tested the speakers with my typical setup with a 48″ distance between the rear of the speaker cabinet and the back wall, I didn’t audition the speakers with the foam bungs.

The Majik 140’s midrange reproduction was beyond reproach: the sound of every instrument with significant content in that frequency region was rendered without colorations and with extraordinary detail. I can’t think of a purer midrange instrument than the clarinet, and the 140 reproduced virtuoso Anat Cohen’s instrument, as recorded on her Poetica (CD, Anzic 1301), with all the subtle inflections of a captivating live performance.

Every vocal recording that I played fared well with the Majik 140’s midrange presentation. Madeline Peyroux’s eclectic range of material on her Dreamland (CD, Atlantic 82946-2) was uniformly presented with sweet, silky, rich verisimilitude. However, I noticed something unusual when I cued up tracks from Tom Waits’s Real Gone (CD, Anti- 86678-2). In this recording, subtle low-level distortion has been intentionally added to Waits’s voice to give it a certain texture. Through the Majik 140, this distortion wasn’t subtle at all; the speaker was so revealing that the distortion seemed highlighted and rather disjointed when juxtaposed against the pristine rendition of the other instruments on the recording.

The Majik 140’s reproduction of jazz guitar was also captivating. In The Poll Winners: Barney Kessel with Ray Brown and Shelly Manne (CD, JVC XR-0019-2), Kessel’s archtop axe had a crystalline, bell-like quality in the upper register, and the rich, woody warmth of his lower-end chording made it obvious that he was playing through a vintage tube guitar amp.

As I’d expected, the 2K tweeter-supertweeter array that the Majik 140 shares with the Majik 109 rendered high frequencies with the same detailed, extended, and natural clarity I remembered from my time with those bookshelf speakers. I sat there analyzing Liam Sillery’s trumpet phrasing on his Outskirts (CD, OA2 22050): His melodic line in “Prana” was brassy and burnished but still light and airy, with all of his unique low-level dynamic articulation clear. The upper harmonic extensions of all of Sillery’s notes were reproduced with definition, air, and just the right amount of metallic bite.

The Majik 140 also mated well with well-recorded violins. Jenny Scheinman’s violin in “The Frog Threw His Head Back and Laughed,” from her 12 Songs (CD, Cryptogramophone CG125), sounded extended and appropriately sharp in the upper register, but also had a sweet, holographic, voluptuous quality throughout its range. Further mining my collection of string recordings, I dug into Evan Ziporyn’s Typical Music (CD, New Albion NA 128). The Linn’s reproduction of this piano trio grabbed my attention as I studied the interplay of members of the Arden Trio: Suzanne Ornstein’s searing, silky violin, and Clay Ruede’s woody, rosiny cello.

The Majik 140’s high-frequency resolution combined with its superb reproduction of transients to make it a breathtaking showcase for percussion recordings. In Second Interlude, from Philipp Vandré’s recording of John Cage’s Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano (CD, Mode 50), the strings are modified to turn the piano into an 88-key percussion instrument. Every thwack, brnggg, and sfffzzt in this performance seemed to pop out of thin air, each sound reproduced within its unique dynamic envelope and a long, natural decay.

The Majik 140’s reproduction of the low end was superb: every bass instrument was reproduced with depth, forcefulness, speed, and no trace of coloration. I analyzed in detail Chuck Israels’ solo in “Our Love Is Here to Stay,” from Bill Evans’s Live at Shelly’s Manne Hole (CD, JVC JVCXR-0036-3). His double bass was warm and woody, with no overhang, and with a sense of drama in its lower register. Moreover, there was nary a trace of timbral change as Israels traversed the instrument’s entire range.

The Majik 140’s high dynamic range capability and realistic bass made it an excellent speaker for loud rock music. In preparation for an upcoming performance with my new R&B band, Souled Out, I’ve been woodshedding the repertoire of Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes, and cranked up the Linns to analyze his original arrangement of “Bad Luck,” from The Very Best of (CD, Philadelphia International/Epic/Legacy 881697 272 88 2). The tuneful interaction of the opening bass line with the drum groove was stunning in its rhythmic coherence—I was unable to sit still. Cranking the volume further still for the title track of Hole’s Celebrity Skin (CD, Geffen DGCD-2 25364), I marveled at the clarity of Melissa Auf der Maur’s powerful bass line, which is easily lost in the mix through other speakers. And that infectious melodic hook in the chorus gave me chills through the Majiks.

A phrase that kept appearing in my notes was dynamic envelope, which was best realized with recordings of large orchestras. In David Chesky’s Piano Concerto, with pianist Love Derwinger and Rossen Gergov conducting the Norrlands Opera Symphony Orchestra (SACD/CD, Chesky SACD326, CD layer), the opening forceful piano passage, followed by the rich, dense transients, gave me the sense of a live orchestra playing in my living room.

A phrase that kept appearing in my notes was dynamic envelope, which was best realized with recordings of large orchestras. In David Chesky’s Piano Concerto, with pianist Love Derwinger and Rossen Gergov conducting the Norrlands Opera Symphony Orchestra (SACD/CD, Chesky SACD326, CD layer), the opening forceful piano passage, followed by the rich, dense transients, gave me the sense of a live orchestra playing in my living room.

The Majik 140 embodied the traditional Linn attributes in spades. With every jazz recording I played, the sense of pacing of the rhythm section was spot on, with perfectly tight phrasing and toe-tapping transients through all instruments’ frequency ranges. A word that kept popping up in my notes was coherence—the sense of musicians playing together in a room and listening carefully to each other. In Radio I-Ching’s rendition of Captain Beefheart’s “Abba Zabba,” from their The Fire Keeps Burning (CD, Resonant Music 004), I could easily hear how Don Fiorino’s growling lap-steel guitar was in near-telepathic communication with Andy Haas’s plunging bass line (actually played on an electronically altered soprano sax).

But the recording with which I best heard all of the Majik 140’s strengths was John Zorn’s Orphée, from his Mysterium (CD, Tzadik TZ8018). Although this musical polyglot is best known for his forays into free jazz, Jewish chamber music, Japanese hard-core, and film music, Orphée is my favorite work of his written in a traditional chamber-music format. The Linns unraveled every subtle detail of Tara Helen O’Connor’s airy flute, Stephen Gosling’s shimmering celeste, and every metallic transient of David Shively’s percussion battery, particularly his mallet instruments and his rich, clear, resonant bass drum.

All Linn

Linn requested that I also listen to the Majik 140 using their Majik DS-I networked D/A integrated amplifier, which Art Dudley reviewed in the March 2011 Stereophile. The request reminded me of a conversation I had over 20 years ago with the very astute Leonard Belleza, of New York City’s Lyric Hi-Fi. As we talked about Linn’s Sondek LP12 turntable, he told me that “Linn components are designed to sound their best when mated with other Linn components.” I approached the Linn-Linn pairing with some enthusiasm.

Using a test pressing of my jazz quartet Attention Screen’s new album, Takes Flight at Yamaha (CD, Stereophile STPH021-2), I compared the Majik DS-I’s amplifier section against my far more expensive combo of Audio Valve Eclipse line stage ($5699) and Audio Research Reference 110 power amp ($10,995)—a comparison even more lopsided when you take into account the fact that a significant portion of the DS-I’s price ($4200) is accounted for by functions and features other than amplification. Overall, the DS-I let the strengths of the Majik 140 speaker shine through. Most important, the speaker’s timbral neutrality was retained, and its superb reproduction of transients were left intact. Moreover, the DS-I let the 140’s full dynamic envelope shine, while nicely controlling the speaker’s bass.

There were some shortcomings compared with my more expensive tube rig, however. In “Sleeping Metronomes Lie,” my piano introduction sounded natural, but was a bit more veiled, with a touch of tension and brittleness, in the more highly modulated passages that came later. The Yamaha AvantGrand N3 electronic piano I was playing also sounded a bit less “woody” and more mechanical. In “The Deer and Buffalo God Churches,” Don Fiorino’s acoustic 11-string guitar was delicate and harmonically right, but not as airy as when played through my reference amplification rig.

Comparisons

I compared the Linn Majik 140 ($2995/pair) with Linn’s own Majik 109 bookshelf ($1590/pair) and the Epos M16i ($1995/pair).

As far as the midrange and high frequencies were concerned, the Majiks 140 and 109 sounded virtually identical. Of course, the larger 140 had much deeper bass, as well as superior high-level dynamics. Moreover, the 140 sounded more “relaxed” than the 109, as if it wasn’t working as hard to make music.

The Epos M16i’s reproduction of the midrange and resolution of detail were very close to the Majik 140’s. Although the Epos’s highs were as extended as the larger Linn’s, the latter’s highs were purer, especially with vocal sibilants. The M16i’s bass was natural and very clean; I’d say that its bass extension and high-level dynamic capability were somewhere between those of the two Linns.

Payoff

I was thrilled with my experience of the Linn Majik 140. It was everything I’d hoped it would be: a speaker that retains all the strengths of Linn’s remarkable Majik 109 bookshelf model, but with deeper bass extension, superior dynamic range capability, and a greater sense of ease. My conclusions are summed up in two lines lifted from my listening notes: “No compromises in a $2995/pair speaker.” “It doesn’t get much better than this for the money.”

Measurements

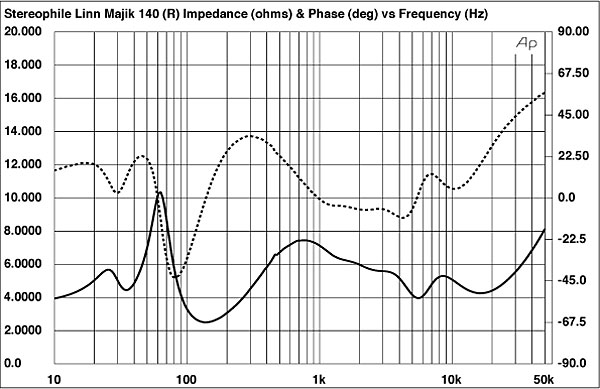

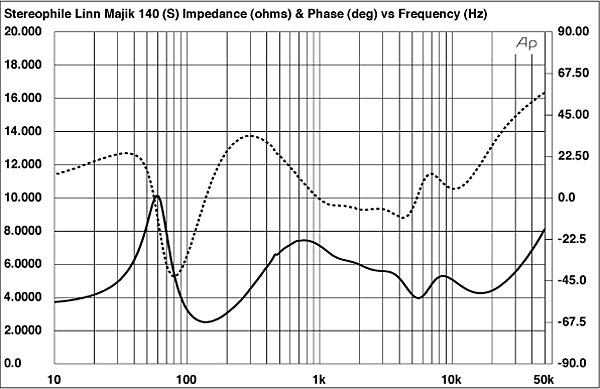

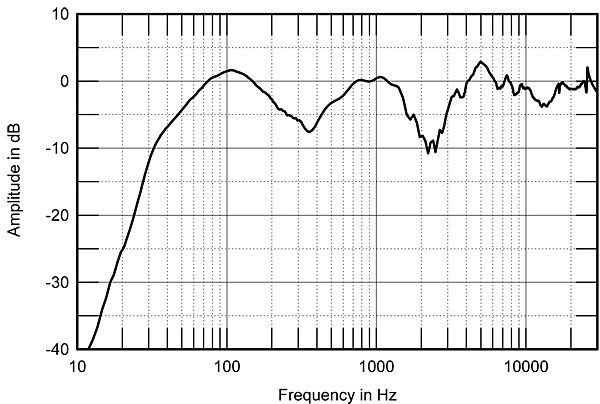

I used DRA Labs’ MLSSA system and a calibrated DPA 4006 microphone to measure the Linn Majik 140’s frequency response in the farfield. For the nearfield responses, I used an Earthworks QTC-40. All farfield measurements were taken on the supertweeter axis, which is 36″ from the floor—a typical ear height for seated listeners, we’ve found. I estimated the Majik 140’s voltage sensitivity on this axis as 88.1dB(B)/2.83V/m, which is slightly above average but conforms with Linn’s specification. However, the Linn is drawing more than 1W from the amplifier at this voltage level. Its impedance drops below 4 ohms in the lower midrange and upper bass, reaching a minimum value of 2.5 ohms at 138Hz. There is also a combination of 5 ohms and 43° capacitive phase angle at 84Hz. The Majik 140 will need to be used with an amplifier rated at 4 ohms to get the best performance from it. With the port on the rear panel sealed with the supplied foam plug, the impedance is identical to that shown in fig.1 above 90Hz, but below that frequency has the single magnitude peak typical of a sealed enclosure with a tuning frequency of 59Hz (fig.2).

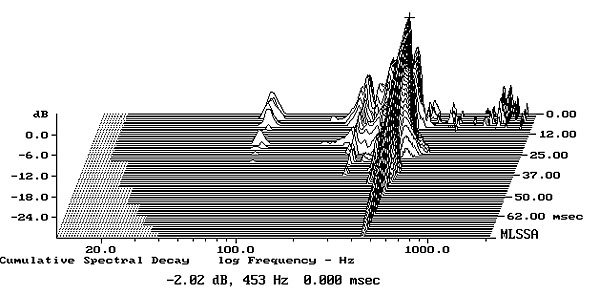

A suspicious-looking wrinkle in the impedance-magnitude trace implies the existence of some sort of resonance between 400Hz and 500Hz. Investigating the cabinet’s vibrational behavior with a simple plastic-tape accelerometer revealed the presence on all surfaces of a strong mode at 453Hz (fig.3). Playing the half-step–spaced toneburst track from my Editor’s Choice (CD, Stereophile STPH016-2), I could readily hear this resonance with a stethoscope, but it was much harder to hear from the listening position with music playing. The resonance is of very high Quality Factor (Q), meaning that to be fully excited, it needs to be stimulated by a number of cycles of the exact frequency equal to the Q. It is possible, therefore, that this resonance measures worse than it sounds, though I felt male voices had a somewhat overwarm presentation that perhaps could be laid at the feet of this misbehavior.

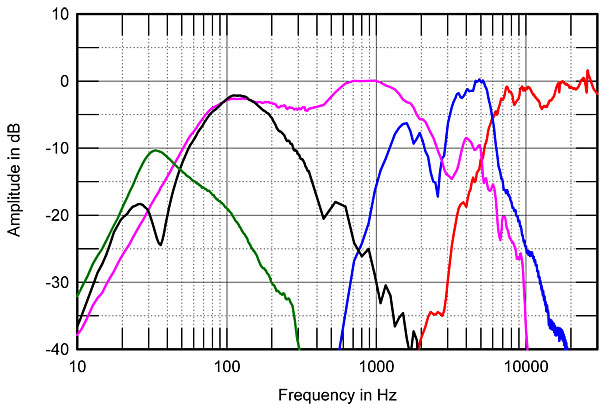

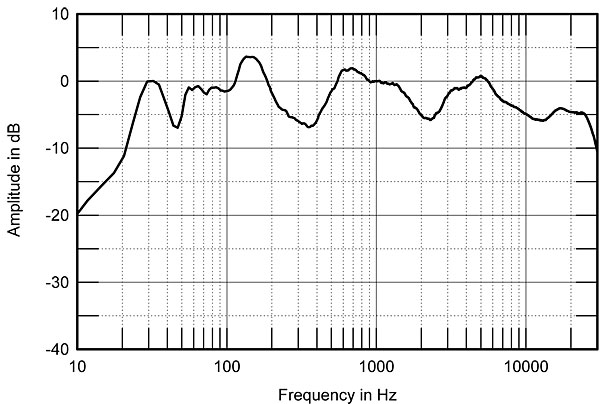

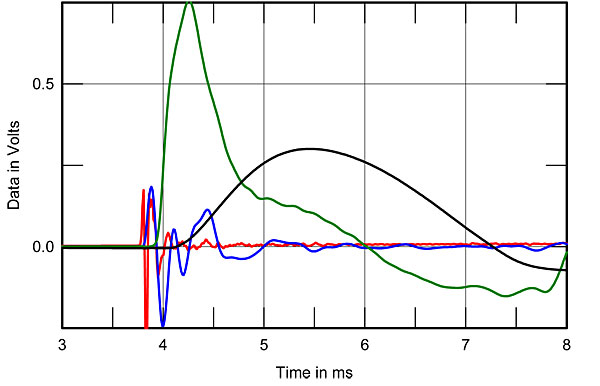

The fact that the Majik 140 has four pairs of binding posts, to allow quadamping or quadwiring, allowed me to measure each of its four drive-units individually. The results are shown in fig.4. The supertweeter (red trace) rolls in sharply above 6kHz as specified, and is flat on axis within its passband. The tweeter (blue trace) rolls off above 6kHz with an equally steep slope, but, like the tweeter of the Linn Majik 109 (reviewed by Bob Reina in May 2009), its in-band behavior is disturbed by a suckout. The 140’s tweeter is actually worse in this respect than the 109’s (see fig.3 at http://tinyurl.com/47hl9u4), but as in the 109, this results in a suboptimal crossover to the midrange unit (magenta trace), at least on axis. The midrange unit’s output bumps up in the upper midrange, and its upper-frequency rolloff is disturbed by a small peak between 4 and 5kHz, but its output is otherwise well behaved. At the other end of the audioband, the midrange unit rolls off below 100Hz with the second-order, 12dB/octave slope typical of a sealed enclosure.

Linn describes the Majik 140 as a four-way design, but you can see in fig.4 that the woofer’s output actually duplicates that of the midrange unit in the 80–160Hz octave, rolling off with a second-order slope above that region. The woofer’s response has a sharp notch at 36Hz that the impedance-magnitude trace in fig.1 confirms is the tuning frequency of the rear-facing port (footnote 1). The output of the port itself (green trace) peaks between 25 and 50Hz, suggesting good low-frequency extension. When I listened to the 1/3-octave warble tones on Editor’s Choice, the 140’s output was respectable down to the 40Hz band, with still some useful bass output apparent at 32Hz. Commendably, there was very little “doubling” audible; the Majik 140’s woofer must produce relatively little distortion. With the reflex port sealed, the woofer’s low-frequency rolloff (not shown) is almost identical to that of the midrange unit.

The trace above 300Hz in fig.5 shows how these individual responses sum on the supertweeter axis in the farfield. The most noticeable features are the two large suckouts, one each in the lower midrange and low treble. The latter was expected, as it results from the suboptimal crossover between the tweeter and the midrange unit. The former surprised me enough that I checked both samples of the speaker and repeated the measurement, only to get the same result. The problem is that this suckout lies in the region where quasi-anechoic techniques such as MLSSA have insufficient resolving power to produce definitive results. But I suspect that it arises from the shelving up of the midrange unit’s response seen in fig.4 and the reinforcement of the midrange unit’s output by the woofer’s in the upper bass, the combination leaving the lower midrange with insufficient energy to blend evenly.

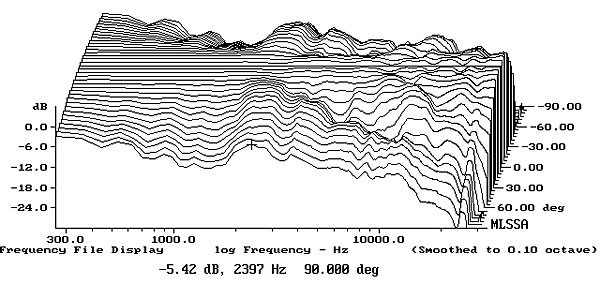

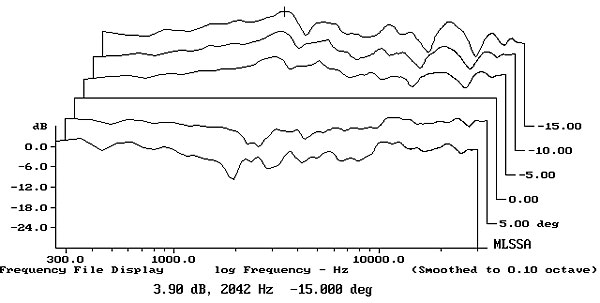

Figs.4 and 5 concerned the Majik 140’s on-axis behavior, but the effect of that behavior on a loudspeaker’s sound quality can’t be considered in isolation; the speaker’s dispersion also needs to be taken into account. Fig.6 shows how the Majik 140’s response changes to the speaker’s sides. The apparent off-axis flare at the cursor position in this graph (2.4kHz) indicates that the on-axis suckout in this region tends to fill in to the sides, something that also happened with the Majik 109 but to a greater degree. Above 2.4kHz, the tweeter and supertweeter have a narrower radiation pattern than I would have expected, given the small radiating diameter of these drive-units. As a result, the Linn speaker might sound a little too mellow in large, overdamped rooms. In the vertical plane (fig.7), the mid-treble balance improves above the supertweeter axis but worsens below.

To further explore the Majik 140’s somewhat idiosyncratic measured behavior, I set the review samples up in my own listening room. Fig.8 shows the spatially averaged response in my room, with 10 measurements taken independently for each speaker in a vertical rectangular grid measuring 36″ by 18″ and centered on the positions of my ears. The same triple-humped curve seen in the quasi-anechoic response is evident in this graph. However, I didn’t hear the lack of presence-region energy as such; instead, it threw the region between 3 and 6kHz into contrast, making it sound too high in level. The excess was audible with pink noise, and it emphasized vocal sibilance a little. On the other hand, the measured lack of midrange energy was not as audible as I’d expected. Male voices didn’t sound too small, which is the usual effect of a lack of energy in this region. Instead, I felt the balance was both bass-heavy and a little “chromium-plated” in the treble, which suggests that I was actually locking on to the level in the midrange as being correct, and thus hearing the regions on either side as being unduly emphasized.

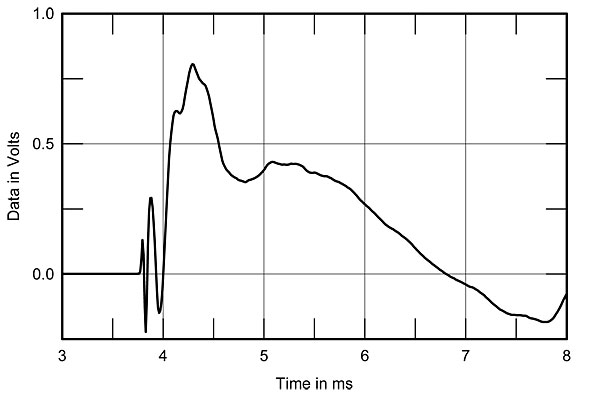

Turning to the time domain, the Majik 140’s step response on the supertweeter axis (fig.9) suggests that all four drive-units are connected in positive acoustic polarity, which I confirmed by looking at the drivers’ individual step responses (fig.10). The supertweeter’s output (red trace) arrives first at the microphone, this blending smoothly into that of the tweeter (blue). However, the arrival of the midrange step (green trace) coincides with the opposite-polarity overshoot of the tweeter’s step, which correlated with the suboptimal frequency-domain integration of their outputs seen in fig.5. Similarly, the lazy arrival of the woofer’s step (black trace) coincides with the negative-going decay of the midrange unit’s step.

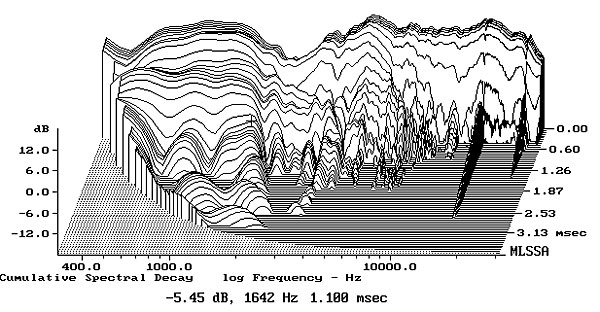

Finally, while some low-level treble hash can be seen in the Majik 140’s cumulative spectral-decay plot (fig.11), the high-frequency region’s decay is generally clean. Things get complicated in the crossover region between the midrange unit and the tweeter, however.

Summing up the Linn Majik 140’s measured performance is difficult. On the one hand, there are some definite problems: that lively cabinet, the sub-optimal drive-unit integration on axis. On the other hand, the problems seemed to step out of the way of the music much of the time. Some listeners will love this speaker for what it does right; others will not be so impressed because of what it does wrong. Bob Reina is definitely in the former camp.—John Atkinson